Sarah Smith and Michelle Kilfoyle

22 December 2021

Charities have taken a huge hit in income during the Covid-19 pandemic. Social distancing has prevented in-person fundraising events, whether fun runs or cake sales, while lockdowns forced charity shops to shut their doors to customers for months at a time.

Of the funding that has made it to charities, there has been a notable shift in donations towards hospital and hospice charities, and away from non-Covid-19 causes.

Our research provides fresh insights for the charitable sector that could shape fundraising strategies and help boost income across the sector post-pandemic.

Lifting or shifting donations?

Fears circulate in the charitable sector that when we give money to one charity, it comes at the expense of donations to others. After all, there is only so much money and, perhaps, good will to go round. But is that really the case? Or can we be inspired to both give more, and give to more charities? Providing evidence from health charities and disaster appeals, research by Sarah Smith from the Centre for Evidence-based Public Services (CEPS) in Bristol’s School of Economics addresses this debate. It shows that there are instances of givers shifting their donations between different charities, and also examples where they expand the number of charities they support.

Health charity donations after severe illness

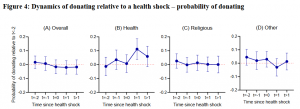

People who have survived a severe health scare are more likely to donate to related medical charities following their diagnosis, a phenomenon known as ‘altruism born of suffering’. A study by Smith and colleagues from Monash University provides evidence on the rate of its occurrence and, shows that this giving does divert spending away from non-health causes.

The research team analysed long-term data (2001-2015) on over 400 households across the US who were asked about their charitable giving and about their health.

In the year following a health scare, namely cancer, a heart attack or a stroke, the probability of donating to health charities went up by 11 percentage points, that is, 41% of this group donated, compared with 30% among those who had not had a health scare. Their likelihood of donating to health charities drops as the years pass, but still remains 6 percentage points higher 2-3 years after the scare.

These donors subsequently gave less money to non-health charities – switching loyalties between good causes, but were not giving more or supporting more charities overall.

Further, the health scares rarely motivated people to give to health charities if they were not already regularly donating to charity. Only 4% of new givers to the health sector had never donated to non-health causes prior to their health shock.

Disaster relief appeal effects on total giving A separate, but related, study revealed very different patterns of giving in the case of disaster relief campaigns in the UK.

Unlike the case of health charities and health shocks, disaster relief appeals trigger a lift in overall donations. People not only give to the campaigns over and above their existing charitable donations, but also go on to donate to other charities that are quite separate to the disaster relief campaign – at least in the short term.

Smith and colleagues from the University of Birmingham and IUPUI in the US studied data on the charitable giving accounts of more than 100,000 UK people who regularly donate through the Charities Aid Foundation (CAF), covering 4.5 million donations to 80,000 charities over 2009-2014.

They focused on six major appeals launched during this time by the UK Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC), including the 2010 earthquake in Haiti and the 2013 typhoon in the Philippines.

Significant spikes in overall donations through CAF were seen after each of these appeals; of the five biggest spikes over the period, four occur after DEC appeals.

Total donations were higher for 14 weeks after each appeal, before returning to normal levels.

Strikingly, donations to other, non-DEC, charities also increased by 10% immediately after each appeal, and these all came from the same people who had given to DEC.

This donation pattern is not unique to DEC appeals. The study found similar results for major annual fundraising telethons, specifically BBC Children in Need, Comic Relief and Sports Relief, where a lift in non-telethon donations also occurred immediately after the events.

A few weeks after the DEC appeals, donations to non-appeal charities dipped below typical levels before returning to normal. However, there was no subsequent drop in donations to non-appeal charities after telethons, suggesting that the degree to which people adjust donations varies by charitable cause.

Altruism vs ‘warm glow’

Smith and colleagues explain the different patterns of charitable giving in the two studies through different motivations for giving.

Health shocks are an intensely personal experience, often life-changing, and donations to health charities are explained by altruistic motivations. The donor cares deeply about the outcomes of the charities’ activities, such as new medical treatments.

Health charities could focus fundraising efforts with patients in the first year following diagnosis, the research suggests, when the salience of the illness and sense of altruism are at their peak.

Giving to disaster appeals and telethons, on the other hand, is explained by a ‘warm glow’ effect. This is the feel-good factor we experience when we help other people. Thus, increased donations to non-DEC and non-telethon charities occur not only because the appeals have acted as a reminder to give to charity, but also because they extend that warm glow feeling.

Building on these findings, the researchers developed a model that tracks the changing influence of warm glow on giving. When the warm glow effect is high, people find giving to charities relativelyeasier, as shown by the disaster appeal research. But when it is lower, perhaps depleted after a string of donations, the cost of giving to charity feels much greater.

The model helps paint a picture of how charities influence each other’s incomes through their collective effects on warm glow and points to how they could best benefit from this. The model could, for example, identify the best timings for campaigns in relation to one another, as well as the timing or targeting of government tax incentives to encourage charitable giving