In our second edition we focus on women, and start by highlighting some of the ways the pandemic has affected men and women differently. Read it here.

Centre for Evidence-Based Public Services

Cutting-edge research with policy impact

In our second edition we focus on women, and start by highlighting some of the ways the pandemic has affected men and women differently. Read it here.

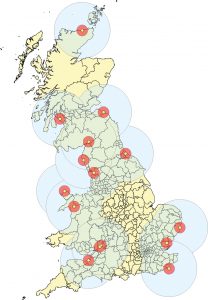

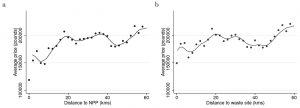

Nuclear power is expected to play a key role in the UK’s Net Zero ambitions by supplying low-carbon energy. However, a new study finds that public fear of nuclear-power plants can heighten local deprivation. Following the Fukushima disaster in 2011, property prices in England fell and deprivation rose in neighborhoods near nuclear-power plants, the research shows. Driven by richer residents fleeing these areas, the study from the University of Bristol’s Centre for Evidence-based Public Services (CEPS) in the School of Economics, in collaboration with the University of Melbourne, suggests that this deprivation is likely to snowball over time based on historic evidence from nuclear-power-plant neighborhoods.

News of the Fukushima catastrophe in Japan sent shockwaves across the globe as Chernobyl-scale radiation levels forced 150,000 residents to evacuate their homes in neighborhoods near the Fukushima-Daiichi power plant. The accident dented public trust in nuclear power in many countries the world over. Yanos Zylberberg of CEPS and Melbourne’s Renaud Coulomb uncovered some of the economic effects of this shift in public attitudes in England. By analysing house prices for the period 2007-2014, using Land Registry and mortgage data, they found that house prices fell by 4.2%, on average, in neighborhoods within 20 kilometres of all eight of England’s nuclear-power plants in the wake of Fukushima. This price drop represents around £9.2 billion in total.

The drop is mostly explained by residents leaving these neighborhoods as they became more fearful of nuclear-power generation, or even first learned that a nuclear-power plant was nearby, following the furor brought by the accident. Tellingly, prices for houses near non-nuclear (oil and gas) power plants were unaffected by Fukushima. The greatest loss was seen for high-value homes, showing that it was richer residents who left these neighborhoods, i.e., those who are more willing ̶ and able ̶ to pay to move to ‘better’ areas.

This flight of richer residents led to a distinct rise in deprivation levels near the nuclear-power plants. On a scale of 0-1 (based on UK Government indices of deprivation), with 0 representing the most deprived neighborhoods and 1 the least, the deprivation rank for nuclear neighborhoods fell by 0.02 points.

Not all neighborhoods were affected equally, however. Those with a higher share of ‘mobile’ jobs, that is, professions that can be easily found in other parts of the region or country, suffered most as workers were freer to move away. Mobile occupations include those in finance, light manufacturing and distribution. Post-Fukushima, house prices dropped by about 8.8% in neighborhoods with the most job mobility, compared with 1.2% in neighborhoods with the least.

This demographic shift is likely to have long-term consequences which are not limited to an event as extreme as Fukushima. Further analysis by the study shows that the share of low-skilled workers rose markedly over three decades (1971 ̶ 2001) in neighborhoods of England where new nuclear-power plants opened in the early 1970s. This ‘rich flight’ trend is, again, far more pronounced in neighborhoods with a highly mobile workforce. The loss of richer residents has negative knock-on effects for the residents who remain, the study warns; their departure may lead to the loss of amenities or employers who need skilled workers, for instance.

The study, thus, sheds lights on a cost imposed by the nuclear industry on local communities in England, although also acknowledges that the sector’s full range of costs and benefits – such as effects on energy prices and climate change impacts – are not assessed. Further, its findings are not true of all countries. Other studies have found similar patterns in Germany and Switzerland, for example, but not in the USA and Sweden. Local context, such as risk perception, insurance coverage and the local composition of jobs, shape nuclear-power plants’ neighborhood effects.

In addition, the study provides insights for policymakers tasked with reviving towns and regions through place-based policies introduced under leveling-up strategies. The findings indicate that areas with highly mobile workers are less resilient in the face of local shocks, such as the arrival of unpopular amenities. But the researchers also caution that places with a non-mobile or overly specialised local labour force may also be highly vulnerable to economy-wide shocks.

Described as the ‘Shadow Pandemic’ by the UN, the global rise in domestic violence against women since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic is a huge cause for concern. New research further emphasises the urgent need to tackle domestic violence by exposing the scale of its devastating effects on the children of women who suffer at the hands of their partners. The large-scale study, which draws on data from half a million families across the developing world, finds that children born to victims of domestic violence are more likely to die by the age of five than children of mothers who do not. Further, women who experience violence endure more stillbirths.

Even before the pandemic, 1 in 3 women across the world experienced physical or sexual violence mostly by an intimate partner, with rates particularly high in developing regions such as Central sub-Saharan Africa (65.64% of women) and South Asia (41.73%). In 2020, the UN estimated that global cases rose by 20% during lockdown.

This study provides further evidence on the costs of domestic violence by highlighting the damage inflicted upon the wider family, specifically children. Zahra Siddique of the University of Bristol’s Centre for Evidence-based Public Services (CEPS) in the School of Economics, in collaboration with Samantha Rawlings of the University of Reading, analysed the results of 54 Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) carried out in 32 developing countries between 2000 and 2016.

Collectively, these surveys interviewed around 500,000 women aged 18 to 49 on issues including domestic abuse, births and deaths of children, and pregnancy loss. Interviewers used robust protocols to help participants feel safe and comfortable and maximise the honesty of responses. Twenty-nine per cent of the women reported experiencing physical abuse at some point in their life , while 9% reported experiencing sexual violence.

A host of factors lead to higher death rates among children of mothers who have experienced domestic abuse. In developing countries, families with abusive members tend also to be poorer and less well-educated; all these factors heighten the risk of children dying.

However, Siddique and Rawlings’ research methods allowed them to disentangle the effects of these factors to put precise figures on the damage inflicted by domestic violence alone.

Death rates within the first 30 days of life for children whose mothers experienced physical abuse were 3.7%, compared with 3.0% for children of non-victims. Siddique and Rawlings attribute a significant fraction of this difference – 0.4 percentage points – to the physical abuse. This accounts for around 4,500 deaths among the 1.14 million babies included in this part of the study.

Further, children of domestic-violence victims were 0.7 percentage points more likely to die within a year, and 1.0 percentage points more likely to die within five years of being born. This means that domestic violence led to the deaths of 7,600 babies (of 1.09 million studied) before the age of one, and 8,500 deaths (of 0.86 million children studied) by the age of five.

Most deaths occurred in families where the women experience frequent violence, as opposed to occasional violence.

Further, mothers who experience physical domestic violence were 1.4% points more likely to suffer stillbirth than women who are not victims, with a similar picture emerging for sexual violence.

To help pinpoint the impact of domestic violence on mortality rates, the researchers estimated the influence of ‘unobservables’, that is, differences in characteristics between victims and non-victims that cannot be measured in the data, but can affect mortality rates. They found that the effect of these factors would need to be much larger, by 2-3 times, to be able to completely rule out domestic violence as the cause of the deaths – giving confidence that violence did explain the higher death rates. These behaviours are likely to arise from extreme stress levels, and the study recommends deeper investigation into these factors to better understand the links between domestic violence and childhood mortality.

Michelle Kilfoyle – CEPS Blog Science Writer

Zahra Siddique – Associate Professor of Economics, University of Bristol