What can we learn about the evolution of neighbourhoods from historical maps? And why is the east side of a city often poorer than the west?

Author: Yanos Zylberberg

A striking feature of cities around the world is the large disparity in neighbourhood composition – who lives where – often reflecting long-term segregation. Bristol is no stranger to these extreme inequalities with the deprived neighbourhoods of Barton Hill or the Dings just a few miles from the affluent Clifton neighbourhood. New techniques to digitise the information contained in historical maps of the city can help us understand the how different neighbourhoods have developed, and why such inequalities are so persistent.

What can we learn about neighbourhoods in Bristol from historical maps?

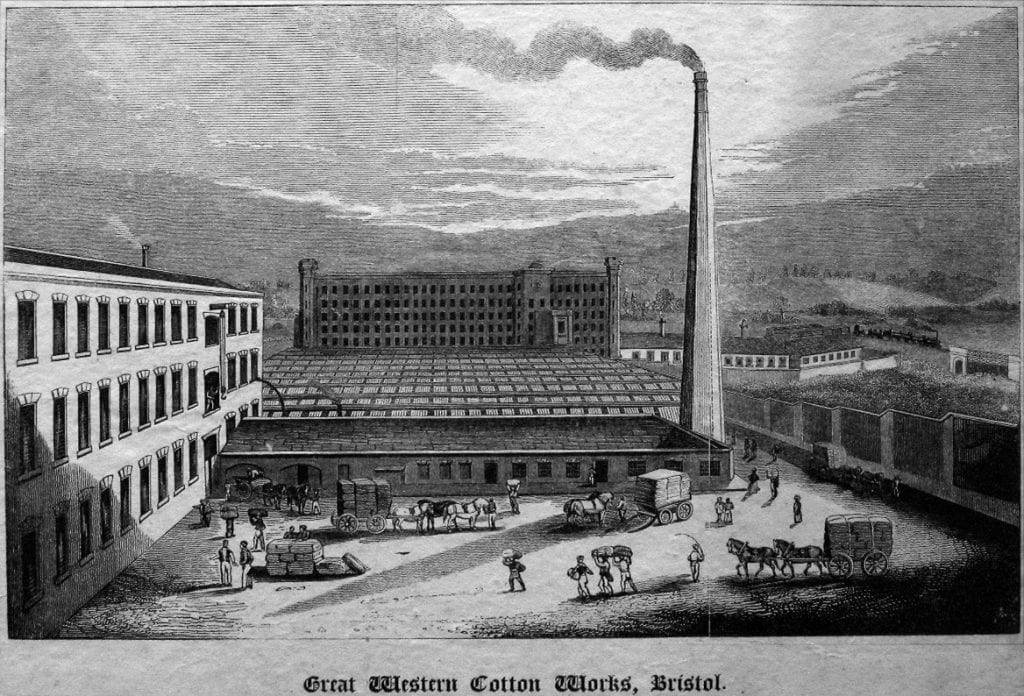

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the Great Western Cotton Factory opened the Barton Hill Cotton Mill in the Barton Hill district, most likely due to the easy access to waterways. The large factory attracted poorer workers from the rural hinterlands, sometimes from much further north. The factory polluted the local area, as did the surrounding chimneys of other factories, foundries and tanneries. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Barton Hill Cotton Mill was still operating; the neighbouring areas had however experienced a prolonged decline in living standards from the dismal environmental conditions, the low quality of public amenities such as schools, the systematic flight of richer residents to other areas, and the mirroring arrival of poorer migrants.

The Great Western Cotton Factory was liquidated in the 1920s, leading to a further decline of the Barton Hill area over the twentieth century. This decline was hardly mitigated by the destruction of the factory and the subsequent land remediation, slum clearances, and other, numerous urban renewal policies. By contrast, the hillside settlement of Clifton remained the richest part of town for the past two centuries, mostly unaffected by the successive transformations of the city through industrialisation, war bombings, and then deindustrialisation.

Why are the east sides of cities poorer?

This story of industrialisation, migration from rural to urban areas, inequalities existing alongside disparities in environmental conditions, neighbourhood segregation and (mostly ineffective) urban policies has not only shaped Bristol, but many British cities. One clear illustration of these underlying forces is the east to west – poorer to richer – pattern of neighbourhoods which can be observed across many cities that were formerly heavily reliant on industry. For example, the east sides of London and Manchester, and internationally, New York City or Paris are notoriously poorer than their west sides. The main mechanism at play is reminiscent of the ‘Barton Hill story’: the prevailing winds, from west to east, meant that the atmospheric pollution from coal-burning factories was mostly driven towards the east side of the city, leading to residential flight by those who could afford it, which still persists today.

While this story of disparities within cities appears to be straightforward and simple, in fact it is not, and many different factors underlie the evolution of different areas. For example: city residents, including migrants, will care about exposure to environmental pollution to different degrees and have different means of escaping it; the cost of land in different areas can lead to factories increasingly concentrating in (cheaper) polluted areas; people who work in these industries may want to live nearby due to a lack of commuting options despite the worse amenities. Large-scale changes will also play a role over time: environmental effects on surrounding areas through the conversion of farmland to built-up land; the invention of the steam engine and improvements in public transport enabled a greater division of areas into purely residential versus commercial; and slum clearances, war bombings, social housing policies, and gentrification can further tilt the trajectory of neighbourhoods.

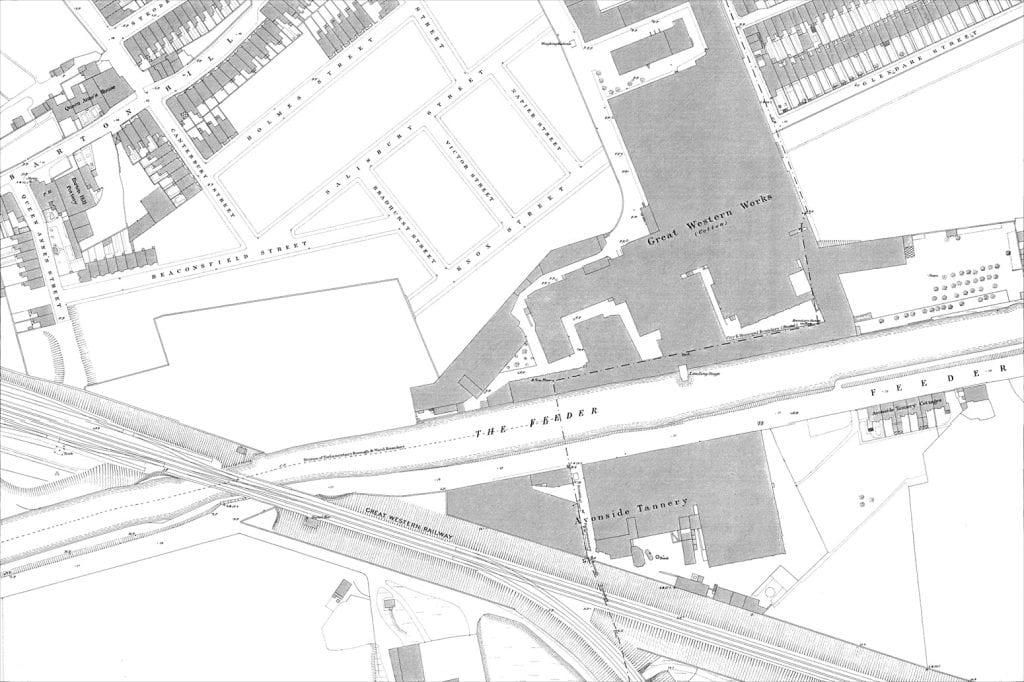

How to turn maps into data

Our research takes a new approach to try and shed light on these mechanisms – using maps. We are generating unique data capturing the structure of cities combining information from local-level historical Census records capturing the characteristics of residents and workers and data derived from historical maps – the 25 inch to the mile Ordnance Survey maps covering England and Wales. These maps were produced at irregular intervals (approximately every twenty years) between 1880–1960, and were sufficiently precise to report detailed features such as industrial chimneys, lamp posts, or even the structure of gardens for the villas of affluent neighbourhoods – a reminder of the fastidiousness of early Victorian mappers. These maps have the potential to capture a comprehensive, changing image of the city, just like Google Maps does today.

Digitising these historical maps presents challenges. They are essentially a collection of highly unorganised information: writing, symbols, lines/segments, or coloured/striped surfaces, which have to be interpreted and converted into data. To do this, the research is using methods that rely on the latest innovations in visual recognition and machine learning to identify a collection of features that are important to understand the location of production, public amenities, and housing – e.g., industrial chimneys, factories and their names, market halls, corn exchange, schools, theatres, prisons, churches, union workhouses, roads and their names, train stations etc.. The resources produced can then be used by those interested in urban development to better understand the trajectory of their cities and how early policy decisions can leave an imprint in the very long run.

The project will create an interactive map of Bristol which combines the information drawn from the analysis of the historical maps – pollution imprints, neighbourhood composition and urban renewal activities – with oral histories from two Bristol neighbourhoods, Barton Hill and the Dings/St Philips. The data on industrialisation, pollution and slum clearances will also be added to the website “Know Your Place” and help connect it to communities for urban planning. More Broadly, the resources can be used to inform policy decisions through a deeper understanding how different neighbourhoods have developed, and why inequalities are so persistent.