Photo Credit: Tokyo Electric Power Co., TEPCO

Dr Yanos Zylberberg and Michelle Kilfoyle

26 October 2021

Nuclear power is expected to play a key role in the UK’s Net Zero ambitions by supplying low-carbon energy. However, a new study finds that public fear of nuclear-power plants can heighten local deprivation. Following the Fukushima disaster in 2011, property prices in England fell and deprivation rose in neighborhoods near nuclear-power plants, the research shows. Driven by richer residents fleeing these areas, the study from the University of Bristol’s Centre for Evidence-based Public Services (CEPS) in the School of Economics, in collaboration with the University of Melbourne, suggests that this deprivation is likely to snowball over time based on historic evidence from nuclear-power-plant neighborhoods.

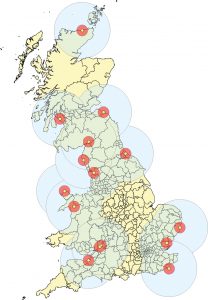

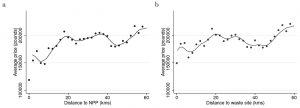

News of the Fukushima catastrophe in Japan sent shockwaves across the globe as Chernobyl-scale radiation levels forced 150,000 residents to evacuate their homes in neighborhoods near the Fukushima-Daiichi power plant. The accident dented public trust in nuclear power in many countries the world over. Yanos Zylberberg of CEPS and Melbourne’s Renaud Coulomb uncovered some of the economic effects of this shift in public attitudes in England. By analysing house prices for the period 2007-2014, using Land Registry and mortgage data, they found that house prices fell by 4.2%, on average, in neighborhoods within 20 kilometres of all eight of England’s nuclear-power plants in the wake of Fukushima. This price drop represents around £9.2 billion in total.

The drop is mostly explained by residents leaving these neighborhoods as they became more fearful of nuclear-power generation, or even first learned that a nuclear-power plant was nearby, following the furor brought by the accident. Tellingly, prices for houses near non-nuclear (oil and gas) power plants were unaffected by Fukushima. The greatest loss was seen for high-value homes, showing that it was richer residents who left these neighborhoods, i.e., those who are more willing ̶ and able ̶ to pay to move to ‘better’ areas.

This flight of richer residents led to a distinct rise in deprivation levels near the nuclear-power plants. On a scale of 0-1 (based on UK Government indices of deprivation), with 0 representing the most deprived neighborhoods and 1 the least, the deprivation rank for nuclear neighborhoods fell by 0.02 points.

Not all neighborhoods were affected equally, however. Those with a higher share of ‘mobile’ jobs, that is, professions that can be easily found in other parts of the region or country, suffered most as workers were freer to move away. Mobile occupations include those in finance, light manufacturing and distribution. Post-Fukushima, house prices dropped by about 8.8% in neighborhoods with the most job mobility, compared with 1.2% in neighborhoods with the least.

This demographic shift is likely to have long-term consequences which are not limited to an event as extreme as Fukushima. Further analysis by the study shows that the share of low-skilled workers rose markedly over three decades (1971 ̶ 2001) in neighborhoods of England where new nuclear-power plants opened in the early 1970s. This ‘rich flight’ trend is, again, far more pronounced in neighborhoods with a highly mobile workforce. The loss of richer residents has negative knock-on effects for the residents who remain, the study warns; their departure may lead to the loss of amenities or employers who need skilled workers, for instance.

The study, thus, sheds lights on a cost imposed by the nuclear industry on local communities in England, although also acknowledges that the sector’s full range of costs and benefits – such as effects on energy prices and climate change impacts – are not assessed. Further, its findings are not true of all countries. Other studies have found similar patterns in Germany and Switzerland, for example, but not in the USA and Sweden. Local context, such as risk perception, insurance coverage and the local composition of jobs, shape nuclear-power plants’ neighborhood effects.

In addition, the study provides insights for policymakers tasked with reviving towns and regions through place-based policies introduced under leveling-up strategies. The findings indicate that areas with highly mobile workers are less resilient in the face of local shocks, such as the arrival of unpopular amenities. But the researchers also caution that places with a non-mobile or overly specialised local labour force may also be highly vulnerable to economy-wide shocks.

Dr Yanos Zylberberg – Associate Professor, School of Economics – University of Bristol

Michelle Kilfoyle – CEPS Science Writer