Michelle Kilfoyle and Patrick Arni

10th November 2021

Rising healthcare costs have intensified the focus on nudging the public towards healthier lifestyles. But what if you mistakenly believe your health to be better than it really is? New research shows that many people are just not as healthy as they think they are, and that this overconfidence hikes up the risk of adopting unhealthy behaviours, such as regularly eating junk food or taking no exercise. Public health campaigns that give individuals a better understanding of their true health status could, therefore, help foster healthier lifestyles, the findings suggest.

For economists, health behaviours can be understood in terms of their perceived costs and benefits to the individual. Even if people know that drinking alcohol or eating junk food carries health risks, many still enjoy doing so.

The weight assigned to either cost or benefit is partly shaped by how healthy we consider ourselves to be in the first place and what we believe our bodies can tolerate. We may reason that “I’m healthy enough to ‘afford’ to drink a little alcohol every day” or “I can’t ‘afford’ the health risks of a couch-potato lifestyle”. The study, co-authored by Patrick Arni of the University of Bristol’s Centre for Evidence-based Public Services (CEPS) in the School of Economics, introduces the concept of ‘biased health perceptions’ to describe how people overestimate their health and how these misperceptions are strongly linked to unhealthy behaviours.

As part of an international research team, with colleagues from the Universities of Bologna and Bonn, and Cornell University, Arni analysed data from three large-scale health surveys from Germany which together covered nearly 7,000 adults..

These surveys included objective measures of health, namely blood pressure and cholesterol readings taken by health professionals, which can be used as proxies for physical health. Further, the surveys questioned the respondents on their health to develop a reliable measure of their overall health status, as well as their health behaviours and perceptions of their health.

The research team used these data to calculate the gap, or biased health perception, between actual and assumed levels of health.

They found that 30% of the respondents were unaware that they had high cholesterol, while 9% did not realise that their blood pressure was high.

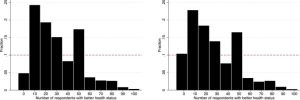

A clear majority of respondents thought that they were as healthy or healthier than most other people of their age when presented with the question: Imagine randomly selecting 100 people of your age. How many of those 100 people would be in better health than you?.

Thirty percent of respondents placed themselves at least 30 places higher in this ranking system than their overall health status would indicate. If the answers had accurately represented people’s true health, then they would have been spread more evenly across the distribution..

The analysis revealed clear correlations in the data between biased perceptions and behaviours. Respondents who were overconfident in their health were more likely to have unhealthy lifestyles, in that they were more prone to eating junk food, drinking alcohol daily, taking no exercise and not getting enough sleep.

For instance, 54% of the respondents who were unaware that their cholesterol levels were high did no exercise at all, compared with 43% of those who were aware of high cholesterol levels. These biased respondents were also 50% more likely to drink alcohol daily, and to have higher BMIs.

Further, 50% of people who overestimated their health in relation to other people did not exercise at all, compared with the 30% who accurately or underestimated their health.

The findings point to several public health interventions. Those with biased health perceptions could be targeted for public health campaigns aimed at reducing risky health behaviours. Regular health check-ups and screenings, in addition to nudging people to seek regular feedback about their health, could also be effective.

Interestingly, biased health perceptions were not linked to smoking habits. This is probably because addiction to smoking overrides any calculations of costs to health. Hence, public health campaigns that focus on the health costs of smoking are likely less effective at curbing tobacco consumption than tougher regulatory measures, such as smoking bans.